March 25, 2024

In my view, the “who hasn’t dreamt of having a real conversation with an NPC” discourse should remind us of the famed “who hasn’t dreamt of living inside their game” discussions we’ve had about VR in the 2010s. It’s a technologist’s dream, but not something anyone will use.

Why, in Mesopotamia, circa 6000 BCE, do people congregate around campfires to hear stories? Because they are getting at something. Because in a sense, we are waiting for the bard, the elder, the priest to impart some form of wisdom. This story is why this goddess fell and how we’re susceptible to love. That story is what happened to a raven and a fox and how we’re susceptible to flattery. They aren’t just arranging words together into nice sentences, rhythms and songs; they are getting somewhere, preferably somewhere deep. What’s the point? Unsure, but there’s one down the line, and that’s why we pay attention.

This deeply ingrained expectation of intent is, I feel, the foremost driver of attention. One would argue that the journey of verbs and convolutions of rhymes is indeed the important part, but the destination is the drive. Otherwise, why, when we can already generate 2000h AI Mozart symphonies (that people can hardly tell apart from the real thing) does nobody listen to them? Not even the staunchest AI enthusiasts do, because while AI can copy the journey, it all feels pointless. It’s going nowhere, 2000 hours away.

The game Facade accomplished the dream of “having conversations with NPCs” in 2005, and while Michael Mateas and Andrew Stern did a pretty impressive job, the tech they made for the game did not catch on. For good reasons. The game still “holds up” one could say. For a pre-LLM era conversational AI, it pulls a bunch of clever tricks to play around its limitations, but it’s still playable. And bland. And in Facade, the conversation is the whole point.

Screenshot from the game Facade (2005) depicting the two main characters, by Procedural Arts

In contemporary dialogue heavy games, the conversations are not the point. They are essential, they are the journey, the flow, the currents that push players along the story, but that’s not why people play The Witcher, Disco Elysium, Assassin’s Creed, or Baldur’s Gate 3. If you’ve ever written for games, you know that most of it is just pushing players along. You need the blacksmith to feel alive, but you don’t need her to give you an exposé on the various types of metal found in the region.

The blacksmith’s lines serve a function. Remember, games are operas made out of bridges and dialogue is not only form, but also function. The added value of a 2000 hours dialogue with the blacksmith is the exact same as the 2000 hours of Mozart-like AI symphony: null. And it’s not only “not making the game better” it is actively making it worse. Open world games already feel too open, too loose, and losing players in sub-plots that typically go nowhere is a good way to disengage them. You had an epic quest, but on the way you stopped to gather herbs for the farmer’s daughter and now you’ve completed it and… Where were you?

Screenshot from the game The Elder Scrolls 5: Skyrim (2011) depicting a blacksmith at work, by Bethesda Game Studios

Once you close the game and go to bed with a happy farmer’s daughter thanking you for a job well done, if you’ve lost track of the main plotline, you won’t be coming back tomorrow. Not because the game is bad, but because nothing is driving you back in. It’s one of the reasons why we see such abysmal completion rates for so many great games: the bard, the elder, the priest lost their train of thought and told meandering sub plots that ended in so many culs-de-sacs that they seemed like they had nothing deep to say in the end.

Now some people might argue that AI could be limited, much like a real blacksmith, it would tell you to go to hell after a few questions. But now, you’re not writing video games, you’re writing games for real life. You see, real life games are subtractive and video games are additive. In a real life game, the whole of reality is open to you, and you subtract : in soccer you can’t touch the ball with your hands, you can’t run outside the line, you can’t hit people. You remove possibilities. In video games, you build from the ground up. The only things that are possible are explicitly stated by you in the code. If you don’t want something to happen, just don’t put it in.

Writing today works very much the same, if you don’t want something said, just don’t say it. But if you’re writing an AI blacksmith? You must now write their backstory AND an unending list of things they’re not supposed to say or know or divulge or get lost in. There may be much more work in creating the AI blacksmith than in writing a few throwaway dialogue options. Multiply that by a few hundred characters.

Not to mention the base input problem. Go ahead, type in your query to our friendly blacksmith on your Xbox controller. Or record it via voice chat if you’d prefer (meaning you have a connected mic enabled headset and not too much noise around you). Choosing between 3 cryptic outcomes in a dialogue wheel will probably seem more pleasant if less customizable.

I wish all of this could be overcome. In 2014 I wrote an article about Justwalkingism, the art movement of “walking simulators” and Justin Smith made Desert Golfing, one of my favorite games out of some elicited thoughts. I hope with all my heart that people will read this article and exclaim “I can fix that, I can make that game. With enough tokens, with enough parameters, I can find some fun to be had here!”.

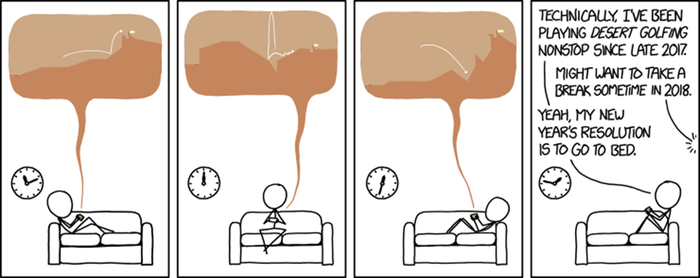

XKCD comic number 1936 by Randall Munroe depicting him extensively playing Desert Golfing

But while I feel that most of the problems I’ve outlined (loss of cohesive vision and story purpose, no point-subplots, writing extensive backgrounds, unending limitations for each character and input problems) can probably be fixed somewhere in the future, the whole debate feels like another round of “VR is the future”. VR is cool, VR is awesome, but VR is niche. VR is an 80s dream that we had to pull billions of dollars into to realize it wasn’t that desirable. Before these marvelous technological accomplishments, one could’ve argued “people will want to do this or that with VR”, but now, we have it, and it does not seem that people actually do want to do anything with it. Even with Apple’s might behind it, VR is still that niche experience where you get into the right conditions, at the right time, and like a Guitar Hero party, you take the hardware out for a spin before putting it back in a cupboard, letting it collect some more dust.

Promotional photo of the Apple Vision Pro depicting a woman lounging on a couch with the Apple Vision Pro VR headset on.

I’m sure some games will be built around AI dialogue. I’m sure they will attract the exact perfect player base and make them very happy, just as I’m sure some people enjoy their VR headsets on a daily basis. But my cautious enthusiasm for what’s possible with AI writing is not born out of a fear that AI chat NPCs as a tech won’t be doable, I just think nobody will care. Why listen to stories if nobody’s telling them.

Read more about:

Featured Blogs

About the Author

You May Also Like