This Way Madness Lies mingles community Shakespeare plays and magical girls, having you travel to dimensions based on the Bard’s works in order to duke it out in fast, but challenging turn-based battles. I don’t recall a giant plant in Romeo and Juliet, but given the light humor of the world and its heroines, I was inclined to accept this new interpretation.

Game Developer had a chat with Robert Boyd and Bill Steinberg of Zeboyd Games to talk about how the game was shaped by a desire to make something his kids could play, how they delve into character using the abilities of the heroines, and how off-beat gameplay ideas can help give you an edge in a crowded game space.

This Way Madness Lies (TWML) ties Shakespearean theater and magical girls together. Can you tell us a bit about how this idea came about? What made you feel these elements would work well together?

Robert Boyd: One of my favorite series is Persona which has a lot of similarities to the magical girl genre. There aren’t many actual magical girl video game series out there, though, and most of what exists is aimed at older otaku. So, I wanted to make one that was fun for all ages so that my kids could enjoy it too.

Most magical girl shows have some sort of theme and my wife suggested Shakespeare since there are a lot of strong women in his plays.

You mentioned that you were looking to create something your kids could enjoy—that audiences of all ages could have fun with. How did that affect how you designed the game, story, and combat?

Boyd: It’s a combination of making sure that the lowest difficulty is very easy, it’s hard to get stuck (no permanent character build decisions), and staying away from anything overly inappropriate. That doesn’t mean we sanitize the content though—after all, a lot of kids’ fairy tales can get pretty dark.

What draws you to these interesting mixtures of concepts (like Cthulhu and Christmas or magical girls and Shakespeare)?

Boyd: As an indie developer, it’s hard to get people to notice your games, so off-beat premises like a Christmas game starring Cthulhu is one way to try to counteract that.

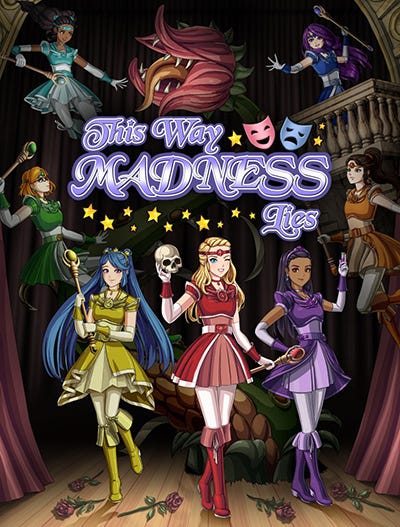

An important part of any magical girl anime is the varied cast. What thoughts went into designing your characters and making them feel unique, visually?

Boyd: We start with archetypes and then try to build them out into more complete characters. My daughters were a big help in trying to make sure that each character had a unique personality and voice. One of my favorites is Miranda who is a total geek with video games and anime—you’ll notice that we show that visually by making her hair reminiscent of Sailor Moon, for example.

Bill Stiernberg: Once we decided the game would have a magical girl theme, we both thought it would be cool to have a ’90s-inspired aesthetic since many people associate magical girls with anime from that era. I looked over the characters’ basic magical elements and decided on the major color scheme for each character. Paulina, who controls Ice, would be light blue for example. Once I had a range of distinct colors for each character, I researched ’90s fashion for their ‘regular’ (non-magical) outfits. I tried to create styles that fit each character’s personality while also matching the color scheme that represented their magical element. From there I directly designed the sprites and iterated on them until they looked unique and interesting from each other, especially the hairstyles since these would stand out more easily on the sprites. Once these “regular” outfits were done, I designed the basic look for the magical outfits—it was a balance as I needed the characters to be easily distinguishable during battle sequences without being too burdensome to animate. So the basic “magical” look was styled after ’90s anime magical girl outfits, and then I further elaborated on the hairstyles and magical headbands for individual sprites. These bright, character-specific colors and varied hairstyles did a lot to help distinguish the cast in battles, without it becoming too burdensome to animate so many individual detailed sprites. Some of the smaller different details are visible in Transformation animations, victory scenes, and the cover art—such as the magical symbols that appear on outfits representing each magical element and given unique styles relevant to a character’s personality.

The cover art for This Way Madness Lies, showing the influence of Sailor Moon and other magic girl anime in greater detail.

It’s equally important to help players connect with those characters, emotionally, through story and dialogue. How do you do that effectively when you’re creating a shorter game? How do you make every moment count in getting to know the cast?

Boyd: With a shorter game, it’s tempting to stuff every scene with as much meaning as possible, but I think it’s important to create downtime and slower moments to make the world feel real and cozy. We made sure to include mundane moments like going to a convenience store for a snack, as well as scenes where you’re just hanging out with the other characters enjoying their company, to give it a real slice-of-life vibe.

What thoughts went into creating the bonding moments (extra character dialogues, intermissions, school time) between the characters?

Boyd: In your typical magical girl anime, there are all sorts of one-shot theme episodes, so we were trying to get that sort of vibe without having to create an entire scenario and dungeon for each one. So, it makes the game feel more like a complete anime season even though it’s a shorter game.

Zeboyd excels at designing punchy, short RPGs that are packed with interesting ideas. They streamline what I often expect from a turn-based RPG experience. What thoughts go into stripping a sometimes over-long, complex genre into something lean and straightforward, but still compelling? How did you do that with TWML?

Boyd: For me, the key parts are dungeons, combat, and story, so we tried to focus on those three elements. The game starts you off in a dungeon with a full party, so there’s no slow build-up there. Multiple difficulty levels let people tailor the experience to fit their preferences. There’s minimal busywork and filler—grinding isn’t necessary, you can freely re-spec your character traits, there are no shops or town exploration, the game is generally linear, etc.

Despite all this, we try to maintain a high level of depth with the combat system and how abilities can transform when the player is in Hyper Mode. We also try to keep animations short and punchy so that they don’t waste your time while still looking good.

Robert, you wrote a blog post for Game Developer a while back where you delve into some of the RPG design philosophies that have fueled your works. You mention the importance of combat strategy and creating interesting fights. How did that affect the design of the character abilities and Hyper Mode in TWML? How did it affect the design of the individual battles and bosses in the game?

Boyd: I think the most important thing to making combat interesting is to give the player interesting choices. That’s why I try to make sure that each character has interesting abilities to use even at the start of the game. Thanks to the no-MP system we use, there’s no incentive to avoid using abilities in order to save up your MP for a harder encounter later on. Also, the Hyper system and the Unites (which get more powerful the longer the battle has gone on) encourage the player to think ahead and debate whether an ability is better used now or later.

With abilities not having an MP cost, battles focus more on strategically using moves at the best times. To that end, how did you design the battles to push the players harder and harder as rounds progress?

Boyd: Generally, with the way our combat system works, we don’t want players to be able to get into a rut and use the same strategy over and over. To this end, every enemy gets more powerful each turn to ramp up the tension as combat continues. How much they increase in power each turn varies from enemy to enemy with some ramping up faster than others. I also have to be careful with this as this means that raising an enemy’s HP indirectly results in them becoming more powerful since it makes it more likely that they’ll stick around for more turns.

You mention the importance of making combat feel fast in that article as well. What design ideas went into speeding up the combat in TWML?

Boyd: Short animations and snappy UI are key here. We also tried to keep enemy HPs from getting too high—I know in our last game, we had a problem with some of the later enemies in the game feeling like they were damage sponges and we tried to avoid that this time around.

Making Unite attacks and special attacks that are visually impressive but snappy seems challenging. How do you make these attacks look spectacular without making them take long to watch?

Boyd: We generally keep the animation lengths short to keep things going. We have a system where enemy abilities that can target the entire party can trigger a short cutscene. Since we thought this would get tiring if overused, we decided to limit it to certain boss moves and not use it in regular battles. Little things like that.

You mention the importance of customization in that article as well. To that end, what thoughts went into the design of the character traits and customizable abilities in TWML?

Boyd: With each character, I try to have a theme for their ability set and then try to come up with a lot of interesting abilities and passives that will fit that theme. One of my favorite games when I was younger was Lunar: Eternal Blue and I loved how they had interesting character archetypes like Ronfar, who is the healer but is also a gambler, or Jean, who is a dancer with a dark past as a martial artist assassin, and then tried to have those personalities shine through in their abilities. I also love the Etrian Odyssey series and how each new entry comes up with new interesting character classes to experiment with.

Can you give us some examples of how the characters’ powers and attacks give a glimpse into who they are?

Boyd: Well, for example, Imogen is the leader, so in addition to strong attacks, I made sure to give her some teamwork-oriented abilities like boosting the power of allies or giving up her turn to another player. Miranda is quirky, so most of her abilities completely transform when she’s in Hyper mode. Viola is gung-ho, so her abilities are focused on speed and combos. Stuff like that.

What challenges come from creating a variety of moves the player only might use? What thoughts go into creating powers and traits that give variety, but are equally important?

Boyd: A large part of this is avoided because our game uses a non-MP recharge system, so even one ability is really good; in most instances, you can only use it once before you need to waste a turn recharging your abilities. Between seven slots for abilities and three slots for traits (which boost stats and give bonus passive effects), we tried to give options for various ways you can build each character to create a synergistic team.

You created multiple difficulty levels for the game. Can you walk us through the design process behind feeling out the difficulty levels?

Boyd: It’s mostly just a gut feeling. I generally play it on the highest difficulty level with an LV and character setup that I think will be typical at that point and see how I do. If I think it feels properly challenging to me, the designer, I’ll set that as the top enemy stats and then adjust the lower difficulties down. And then I get feedback from others on whether the lower difficulties feel good and adjust accordingly.

How has your philosophy on RPG design evolved over the years? What have you added to that design philosophy from over a decade ago, and how does TWML reflect those thoughts?

Boyd: I hope the biggest change in my philosophy of RPGs over time has been to trust the player more. I play games for specific reasons, but everyone is different, and sometimes it’s hard for me to step outside of my opinions and viewpoint. So, I try hard to make our games in such a way that they’ll be fun for many different types of players.