There is nothing wrong with an inherently difficult game. It’s what I’ve built my entire career on, in fact. But the degree to which I was shutting out players from enjoying our games simply due to our staggering difficulty didn’t become apparent until it was too late—and the features we put in to make our games more accessible didn’t address inherent issues. But with new games comes the new opportunity to try again and get it right.

My name is David Galindo, creator of the Cook, Serve, Delicious! series and creative director for Cook Serve Forever, the next game in our seemingly never-ending quest to create the most engaging cooking games ever. While the first Cook, Serve, Delicious! game had an Extreme difficulty mode and was quite challenging towards the end, it wasn’t until the second game that we prided on having a notoriously difficult gameplay experience, and leaned into it heavily with “Prepare to Dine” imagery and images of chefs cooking angrily, tired and exhausted.

There were plenty of other games out there if you wanted an easier time. We weren’t interested in that. Based on the Steam refund data of those who gave a reason for their return, 16 percent of people refunding Cook, Serve, Delicious! 2!! did so due to the game being too difficult, jumping to 20 percent for Cook, Serve, Delicious! 3?!, despite the fact that we did have easier modes to choose from to help scale down the difficulty.

Today I’m going to dig into why our difficulty selections didn’t really work in CSD 2/3 and what we plan on doing for Cook Serve Forever. There are two key areas I’ll be really focusing in on today: the visual makeup of the UI for the games, and our difficulty options that were born out of necessity rather than an inherent understanding of what exactly I was doing.

UI Balancing

We took a lot of care into making a lot of visual accessibility improvements for CSD 3: reducing motion in the backgrounds, colorblind improvements, screen shake toggle, and even removing some visual effects that were causing a few people to have headaches before releasing out of early access. But what I really wanted to do with this new game is break down what, exactly, the player is looking at. Something that I really never took into account is what the player should be looking at vs what they are looking at.

To figure this out, I studied how I played CSD 3 and highlighted areas where I felt the most attention was given by the player to finish a task, vs what other areas provided key info but were not immediately important in any given situation (red indicating an extremely important piece of info, all the way to green which shows unimportant, yet still useful info.)

To break down this image, you have:

Critical Areas

-

Recipe, to know what ingredients are needed.

-

Ingredient pane, to place the ingredient with the correct button press.

Very Important/Important Areas

-

Orders (left side of the screen) with varying importance- some are leaving (indicating customers losing patience and a potential fail for the player), some cooking (which the player must get to before it gets burned), some arriving, some stationary.

-

Holding stations (top of the screen) that lose freshness with every second. Once the freshness expires, the food cannot be used, and some orders on the left side immediately start to leave if there are no other foods of that type in the holding stations.

-

Autoserve ready (the sign on the bottom left of the recipe), indicating the player can flick the stick to serve all orders that are ready to go.

Not Critical

-

Perfect combo count (top left) and the UI stats on the top right that gives player rank, customer count, how many stops are left, and how many strikes they have which will determine the medal they get. These two become more important when chasing for gold medals as they will tell the player when a mistake has been made and when the player should restart a level.

This was an eye-opening exercise for many reasons. The first was something I long suspected—no one was looking at the middle of the screen. Watching streams of CSD 3 I saw quite a few people commenting how they didn’t realize how good the food looked when they played the game themselves. The second is just how dramatically difficult it is for new players to gain an understanding of what is going on. Again, many people in streams coming into the game for the first time almost always remark with “I have no idea what’s happening” and I never saw streamers really explain because it is quite a lot to take in.

I do want to make something clear though: this is not a mark against CSD 3. In fact, this shows just how satisfying it can be when you are locked into the gameplay and you’re able to look and process all of the information at once. Pro players of CSD 3 are incredible to watch as orders are taken and sent out with maximum efficiency. And once you do get the hang of it, a lot of this does become second nature.

The problem is, for a new game to work, you have to add new mechanics, new gameplay, new features, and there is literally zero room to add anything fundamentally new to CSD without removing some part of the core gameplay. Where would I even put it? And so I found that I could tackle both the issue of accessibility and creating a new gameplay dynamic by simply starting over and creating something completely new that hasn’t ever been done before by us.

With this being an entirely different game, I was able to simply start from scratch and build an entirely new gameplay concept while dramatically changing the visual cues and aspects of the game. I wanted something that looked inviting for people to play. At the same time, I wanted something new but not overly complex to look at. There is only one main piece of critical info: the buttons you need to press to get an ingredient on the food. The rest range from non-vital to simply fun UI design.

Ultimately we have to be careful not to oversimplify the game’s mechanics, as we still want that feeling of fast-paced gameplay and being able to ramp up the difficulty quickly for vets. Difficulty is something I’ve been thinking about for a long, long time.

Difficulty Selection

When Cook, Serve, Delicious! 2!! launched in 2017 it was in a rough state; I had coded and not slept in days as I frantically tried to get the game in a shippable state. I didn’t even have mouse support for the main menus. The game rapidly went down in review score, reaching 80 percent as I pledged to do everything I could to fix it (as I was the sole coder on that game).

There was no real time to weigh my options; I was ready to add anything that was suggested within reason to get our review score back up. And with the various patches I started doing every month, that’s exactly what happened, going up to 90 percent where it is today.

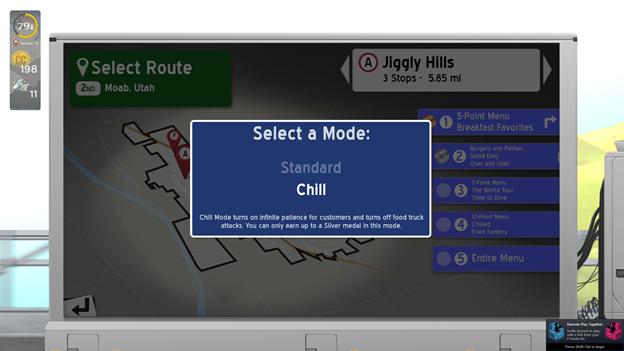

One of the suggestions—something that I would have never considered otherwise—was the addition of an easier game mode. This to me was completely against what our game stood for, but I had no other choice as it was an easy enough addition to have without relying on new assets being created for the game. This is what “Chill Mode” was all about: stopping certain timers that would fail players if they weren’t cooking fast enough and allowing players to cook at their own pace (though you could still fail by letting foods cook too long and so on).

This gave me a false sense of accomplishment. We created an easier difficulty to choose from, therefore our audience has now expanded to those who might not want a much harder challenge, and now I had a totally accessible game for just about anyone. Right?

What I have found however, both in my own playtime and seeing how players interact with our game, is that difficulty selection is inherently flawed. It does not work. It has never worked.

Select This for the TRUE Experience

Let us take Crash Team Racing as an example as I pick it up on the digital store and dive right in. I’m a big racing fan, love Gran Turismo and I like Mario Kart back in the SNES days but can’t really get into the newest ones. I hit start and it asks me to select a difficulty- Easy, Normal, and Hard.

It is fascinating to me that we are asked right before we play a game for the very first time how good we think we’ll be, especially with games that ask to commit to it because you can’t change this option later. I’ve seen gameplay of this game. I’m good at Gran Turismo, not so good at Mario Kart 8, great at Mario Kart SNES. Where exactly does my experience lie in these three options? (CTR is notoriously difficult at its medium setting, as it turns out).

Or let’s take a game like the original Halo and see how they describe their own difficulties:

Easy: Your foes cower and fail before your unstoppable onslaught, yet final victory will leave you wanting more.

Normal: Hordes of aliens vie to destroy you, but nerves of steel and a quick trigger finger give you a solid chance to prevail.

Heroic: Your enemies are as numerous as they are ferocious; their attacks are devastating. Survival is not guaranteed.

Legendary: You face opponents who have never known defeat, who laugh in alien tongues at your efforts to survive. This is suicide.

The first and last difficulties of any game don’t need a descriptor; we already know from the start if this is a game we’ll be playing at the easiest or most difficult selection. Yet Easy already attacks the player for choosing it; sure you will win, but you won’t feel satisfied. This is so common for games at that time and even today. Similarly, Legendary goes all out on keeping players away, knowing that those that want the hardest experience are going to choose this no matter what’s written, and making the player feel even more satisfied when they conquer this difficulty.

The Normal and Heroic difficulties are the ones that people need the most help in choosing, and the descriptors completely fail here—nothing here is really telling me what exactly I’m in for. What it really comes down to is that I am being asked to rate how good I’m going to be at a game, with the penalty being that I’m going to have a much worse time if I select the wrong one.

Ah, but what about games that let you change your difficulty on the fly! Wouldn’t that solve the issue of choosing the wrong difficulty? Well it doesn’t matter because chances are I absolutely won’t change the difficulty once I’m playing!

Looking at our own analytics for CSD 2, players almost never change their preferences once they lock themselves in a difficulty. If I feel like I’m a pro racing player, but want to enjoy myself and come in first often so I select normal, how will I feel if I keep getting 4th or worst? But this is normal difficulty. I am the one that’s bad. I obviously need to keep at it and do better. And so three potential things could happen here: I could get better and actually start to do well in normal, I could get frustrated and just quit, or I can dial the difficulty down while also lamenting the game’s design. You never hear, “oh man I sure like Racing Karts Bonanza, but my racing skills have really deteriorated I suppose and I had to go down to easy.” It’s always “the game was way too difficult/fundamentally broken/I had to go down to easy just to play it” as if it is a negative aspect of the game.

Outside of poorly designed gameplay like, say, rubber banding AI or bad controls, it is not inherently the game’s fault for making this player frustrated when it comes to gameplay. It was the game’s fault for not allowing the player to choose an option that best suited them. Think of it this way: when you keep failing at a game and after ten attempts the game asks if you like to go down to a lower difficulty, how did that make you feel? Frustrated? Angry? Did you actually go down a difficulty?

All of this leads to the two difficulty selections of Cook, Serve, Delicious! 3?! as you can choose between Chill and Standard. I thought I was being clever with not calling it Easy and Difficult. It didn’t matter. People who play on Standard mode and can’t progress almost never fall back to Chill mode, they just give up altogether. And those who chose Chill mode and still had a tough time making it through the game had no other recourse other than to give up. (It didn’t help that, in a way for me to make things “fair”, I didn’t allow chill mode players to earn higher than a silver medal. It was essentially no better than other games calling easy modes hollow and unsatisfying, punishing the player for choosing how they wanted to play.)

The answer to all this, and something we’re still in the process of designing with Cook Serve Forever, is dynamic difficulty given to the player. By giving players greater rewards for choosing harder foods we can allow them to craft their own experiences and make them feel like they’re in control of their own success and failures, rather than leaving it up to what they selected at the start of a gameplay session. While this was something we did in CSD 3, we still had the difficulty ramp to where players could only choose harder foods towards the end of the game, and I think the more ideal experience is to have players choose to ramp it up towards the end—or still play with some of their favorite foods that might not be entirely difficult.

Of course, the challenge there is making sure that the game is properly balanced to allow players of any skill set to be able to run through the campaign in the same amount of time. If we can pull all this off, that means both types of players made it to the end, something that was painfully lacking with CSD 3 with around ~2 percent of players making it to the end stages of the game.

Games for Everyone

My perception of game difficulty has changed over the years, both in terms of how players react to it and how little the game’s core players care about easier difficulties if they wish to play a much harder version of the game.

But it’s not just difficulty in terms of gameplay, it’s also the difficulty of showing the player the information they need on screen in a pleasant and not-overwhelming way. It’s making a game as devilishly simple as possible to lure unsuspecting players into what can be a very challenging, but not frustrating game.

We struck that balance pretty well in the first Cook, Serve, Delicious! game and I’m eager to see if we can capture that same magic. Who would have thought that after ten years of making cooking games there’s still joy in finding new ways to pull it off all over again.