Game Developer Deep Dives are an ongoing series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren’t really that simple at all.

Earlier installments cover topics such as lessons learned from ten years of development with Ingress engineering director Michael Romero, how legendary Dwarf Fortress programmer Tarn Adams updated the game for its official Steam release, and how architect and solo developer Jack Strait made an entire horror game in PowerPoint.

In this edition, Cyanide Studio project manager Diane Quenet and lead game designer Antoine Cazayus tell us how they found the right balance between authentic and streamlined experiences in their cooking sim Chef Life: A Restaurant Simulator.

Hello everybody! This is a “four hands” presentation: project manager Diane Quenet and lead game designer Antoine Cazayus. We work at Cyanide Studio, and we are behind code name “Arrabbiata” or, rather, Chef Life: A Restaurant Simulator.

When Nacon suggested that we work on a restaurant simulator, we were immediately excited by the idea! We had just finished Call of Cthulhu, a game with a dark and gloomy atmosphere, so a title with some color and a lighter tone in an area of interest to us was welcome. We are really excited as developers to be able to present certain aspects of the game.

We began by researching the restaurateur profession and how the culinary world is represented. We found plenty of depictions in the media, be it documentaries, cooking competitions, films, or anime, as well as mechanics in video games. If there are a few true-to-life depictions, such as the excellent film The Chef, most are very colored and phantasmagorical.

We had the opportunity to spend a day immersing ourselves in the CFA Mederic culinary school with chef Julien Chaudun. He showed us the real, and sometimes less glamorous, aspects of the profession, such as the legal and hygienic constraints, shouting during service, the physical difficulty, and the harsh reality of restaurants that go bankrupt.

We were also treated to a cooking masterclass in which, for several hours, we burnt our fingers picking up our scalding gnocchi, froze our hands as they recovered in a bag of ice cubes, and put our muscles to the test on a vegetable mill.

At the end of the day, two things were sure: firstly, that it was time to get into shape and, secondly, that we were going to start work on a subject that was enthralling and very rich!

Because of the unifying nature of cooking, Chef Life caters as much to cooking enthusiasts who know little about video games as it does to hardened gamers who are interested in gameplay that adopts the codes of the restaurant profession. Because of these different profiles, we anticipated our first and main challenge: create a game that pleases and is accessible to such a wide panel of players.

Our job was to find a compromise between this fantasized representation and the hard, but necessary, reality of the profession. In this article, we’ll go over the problems we encountered and the solutions that were implemented to solve them.

Game Overview

Chef Life is an immersive simulation game played in the third-person. The player takes on the role of a chef, owner of their own restaurant, in a feel-good and friendly atmosphere designed to make them feel cheerful.

We offer a fairly complete overview of the profession: management, customization to the point of designing one’s own platings, planning, and, especially, lots of cooking in order to discover and prepare numerous recipes that become more difficult until they reach gourmet level. Your restaurant starts off small, with a few recipes and simple equipment, and you progress, day after day until it becomes a must-eat establishment in town.

How we simplified cooking

‘Understand the superfluous part of cooking for a video game and concentrate on the fun.’ That was our first challenge. First, we analyzed how recipes are created and organized and then how existing video games translated them into gameplay.

In cooking, recipes are a step-by-step process, lists of stages to follow with more or less rigor. There are details of the ingredients, the exact weights, the utensils to be used, and the spices to favor. They take time to be executed, and they require a certain level of attention.

In games, this rigor is either left out in order to favor speed and amusement (like arcade games) or highlighted in order to favor simulation. These two positions did not satisfy us because they were very clear-cut. We wanted to find a balance representing the depth of cooking without overloading our players with information.

Focus on pleasure, avoid toil!

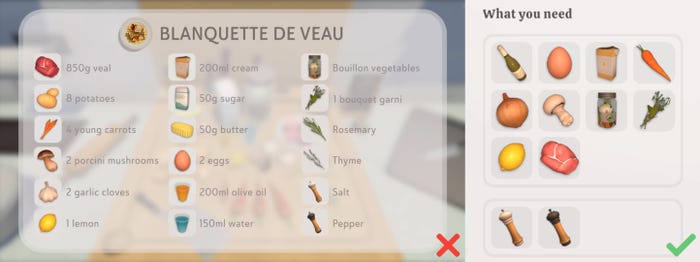

Each recipe begins with gathering the ingredients. Where normally you might have to assemble the right number of vegetables or prepare the exact weight of flour, in Chef Life you are asked to provide one of each item in the recipe. These ingredients are not units but concepts. To make Blanquette De Veau, you are not required to provide 850g of veal and four carrots, but simply the Veal item and the Carrot item.

In this way, we are sure to present a recipe that is realistic in its composition without overloading its execution.

On the left a realistic list of ingredients, on the right the “concepts” of ingredients in Chef Life.

Cooking times were also simplified. Cooking is split into different types: skillet-fried, sauces, bouillons etc. Each type of cooking has a specific length of time. So we avoid having to specify these times individually, and we let the player get used to the times without having to memorize the numerous variations.

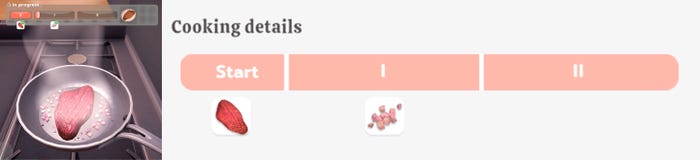

When doing real cooking, ingredients must be added at the right moment in order to produce a uniform dish and avoid under/overcooking. In order to represent this specific feature of cooking in real life, we split it into phases. The “Start”, the “First half of cooking,” and the “Second half of cooking.” You don’t need to know after how many minutes you should add the shallots, just that you need to do it during the “First half of cooking.” We avoid having to require the challenging effort of memorization while still representing the true-life importance of cooking ingredients at different times.

The cooking gauge is divided in three phases. The player starts with the steak, then add the shallot after a moment.

Encapsulate passion

Simplification is not enough; there must be passion. We had to ensure that in-game, when you are at the stove, the passion for real cooking is present.

One of the pleasures of cooking is the sentiment of accomplishment, of beginning a recipe with the basic ingredients and bringing it all together into a sophisticated and elaborate dish. In Chef Life, players must complete the step-by-step processes of recipes from start to finish. In order that recipes are not too long and are fun to play, we removed some sub-stages. However, this trade-off was done in a way that retains a maximum number of stages in order to communicate a feeling of completion.

Cutting, cooking, assembling, and plating a “Caprese with balsamic reduction.”

Other actions, such as cutting vegetables, plating, or scaling fish, are simplified in their visual and gameplay aspects. These “mini-games” can not be failed, are not scored, and take up little time. We call these “cooking manipulation,” and they play a key role in immersion. The player imitates the cutting of an ingredient by moving their thumbstick, thus giving the impression of having completed the action.

Cooking also entails a myriad of actions and iconic techniques that we wanted to replicate in-game. Players must, like real chefs, carry out precise actions that are dictated by the recipe: turn meat over and make sure it’s cooked on both sides, stir a preparation to stop it from sticking, or flambé a dish after adding alcohol. All gestures make cooking what it is and differentiate it from a classic crafting game. That’s why they are at the heart of our cooking gameplay:

Basting a preparation, stirring regularly, kneading the dough.

In real life, cooking can be unpredictable. Even when recipes are followed to the letter, there is always an unforeseen element that requires chefs to show off their expertise to carefully tweak each dish.

We also wanted to represent this aspect in the game. This is where the idea of “Chef Sense” came from, a unique skill of the character that allows them to analyze the dish being prepared and to adjust it delicately. This skill allows you to taste a dish and adjust its seasoning, test the cooking of a dish in the oven until it is perfect, or check a dough so that it is worked as best as possible. Each dish received its own tweak.

Using Chef Sense to perfectly seasoned the prep or to find the perfect baking.

A challenge leveled upwards: how to evaluate a good Chef

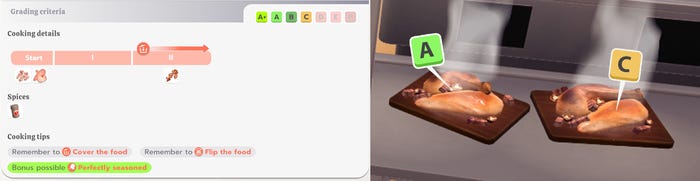

Chef Life is a game with a varied audience, some of whom are new players, unused to the challenges that video games can pose. With this idea in mind, we decided on our philosophy for the difficulty of challenges: “easy to prepare a dish, but complex to execute it perfectly.”

It is almost impossible to make a hash of a dish. The ingredients and stages of a recipe are imposed. So how does the game set a challenge? The devil is in the details. In Chef Life, each recipe is accompanied by a list of “Cooking Tips” that must be memorized and followed to the letter. These “Cooking Tips” are additional, optional stages that, if followed, allow the player to gain a better technical execution score for a dish. So, if everyone can follow a recipe through to the finish, only the most diligent can aim for perfection.

On the left a recipe book with the cooking details. On the right two dishes with different technical grades depending on player’s diligence.

The real difficulty of the game

By taking one’s time and applying all the right chef actions, it is not so difficult to achieve the best technical execution score. However, Chef Life becomes a real challenge when one decides to cook several dishes at the same time. To more easily execute dishes in parallel, we paid particular attention to balancing recipes in terms of equipment required and the length of cooking. In this way, while a soup is slowly simmering, it is possible to start preparing fillets of fish for another recipe. It’s when several recipes are being executed in parallel that forgetfulness, confusion, or error come into play, bringing a demanding edge to the game and giving it its flavor.

Preparing a fish while the broth cooks slowly. Rest in peace, sea bream.

This is even more true during service hours…

All hands on deck! Service hours

All restaurant owners will tell you service hours are times of rush and adrenalin where concentration is key. Translated into a game, it provides a sequence of intense gameplay, contrary to what most players would expect from a simulation game where the pace is slower.

In the game, the restaurant opens its doors at 7 PM, when customers arrive and begin to order dishes from the menu. The player must do their best to serve everybody quickly.

Rush hour!

We got it wrong!

At the beginning of the production, we left an open amount of time before the service phase in order to allow players to get ready and thus remove the stress from this period. However, that produced undesirable consequences: long days where players spend their time preparing plenty of dishes from the outset or an assembly-line production of dishes without taking time to discover new recipes. The gameplay sequence of the service became anecdotal because all the dishes were ready when clients sat down. It also produced a lack of realism because it was possible to prepare a steak in the morning and serve it in the evening.

All the workstations are occupied by food preparation.

One idea we had was to make service times a separate game mode. We didn’t go down that path because it would impair the desired experience; serving customers is a restaurant’s objective. Without table service, it would be a cooking game and not a restaurant game. By retaining this phase, the whole day is built around table service, providing an unavoidable deadline. Therefore, to retain this gameplay sequence and allow the player to feel the “all hands on the deck” rush, we added a few tools to structure the experience.

Preservation

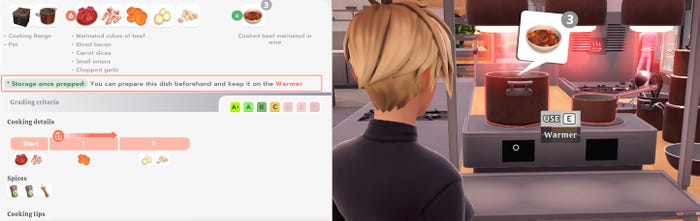

The player has limited storage spaces for his dishes during the preparation phase. When table service begins, all preparations not in a storage space are removed from the kitchen. In this way, we ensure that the player has a limited amount of prepared dishes, requiring them to carefully choose what is prepared in advance. Because the number of dishes prepared in advance is limited, this frees up time for other activities during the day.

We also added other limitations for more realism. In a recipe, certain steps can not be prepared ahead of time. It is, therefore, possible to prepare a sauce, cut a steak and prepare other ingredients, but do the final cooking and plating during service hours.

All the workstations are occupied by food preparation.

Customers

Customers expect to be served quickly, which is represented by a patience gauge. If the “time’s up” is reached, they don’t get up and go, because that would disrupt the planning of an already overwhelmed player. The player just doesn’t earn any bonus during these service hours.

The number of customers self-regulates: the more efficient a player is during service hours, the more customers they receive, increasing service hours and, as a result, the length of concentration. It’s a sort of “word of mouth.” A player having a bit of trouble receives fewer customers and, therefore, finds it easier to manage.

Other tools

The brigade provides significant support during service hours, allowing dishes to be executed in parallel, and is a real help if there are any mishaps.

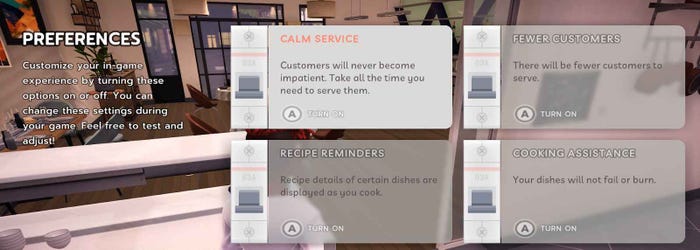

Several help options also allow the game experience to be changed for those who want a quieter time, but without removing the gameplay phase.

Specific game preferences allow you to play as you like.

In conclusion, a player’s organization and choices during the day are rewarded because they are less fazed during service hours even though complexity increases (more elaborate dishes and more customers). This feeling of progression and achievement is truly rewarding, because they feel involved and invested in their role as chef.

A veneer of management

The player is the owner of the restaurant. Management of time and the preparation of dishes is a major part of the game experience, as mentioned above, but that’s not all.

Finances

In France, around 20,000 restaurants open each year, but around 60% go out of business within 5 years (pre-Covid figures). It’s a tough business!

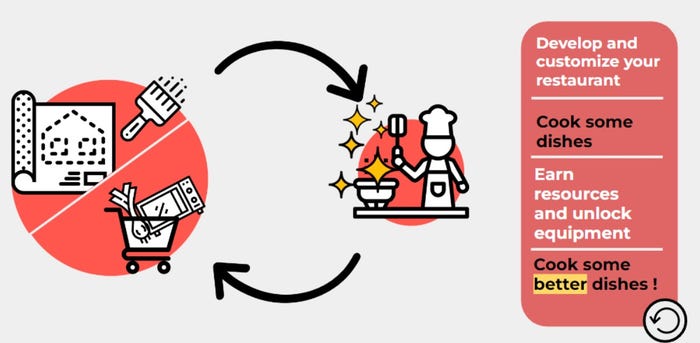

We selected the most representative tasks of a restaurant owner to integrate into the game. The player is in the shoes of a manager, deciding how to allocate the budget, deciding on suppliers, and determining if it’s time to purchase new equipment or to freshen up the decor. Receiving customers brings in money. If mealtimes go well, more money is earned. Money provides the framework for a player’s progression. It’s not there to challenge them, and it’s impossible to go bust. We preferred not to shoulder the player with financial pressures in order that they focus on cooking and be in a virtuous circle of entrepreneurship.

The marvelous circle of entrepreneurship.

Produce and responsibility

A responsibility gauge represents the player’s management choices that are impacted by various factors. To avoid losing money and seeing food go to waste, restaurant owners must carefully manage their stock of produce. The player must buy ingredients from various suppliers, but this produce has an expiration date, so the player must manage their kitchen pantry. High responsibility means more work and cost, but it also means that the brigade is motivated and more effective. These features represent the various aspects of the business while remaining simple to access to allow our player to focus on cooking.

Above: a supplier who sells local ingredients that can increase the responsibility of the player. Below: two sous-chefs, one galvanized and one unmotivated, who work more or less quickly depending on the player’s level of responsibility.

Hygiene

In the restaurant business, respecting hygiene norms is crucial. This assumption was considered in the game. The feature is simple: the more time passes, the dirtier the restaurant gets. To clean the place, it’s like taking candy from a baby! Nevertheless, it requires the player to trade their precious time to ensure their restaurant stays clean. It asks the player to manage their time well.

The player receives a reward or a penalty depending on the state of the restaurant when there is a hygiene inspection. In the same way that the restaurant won’t close down for financial reasons, it won’t close down for hygienic reasons.

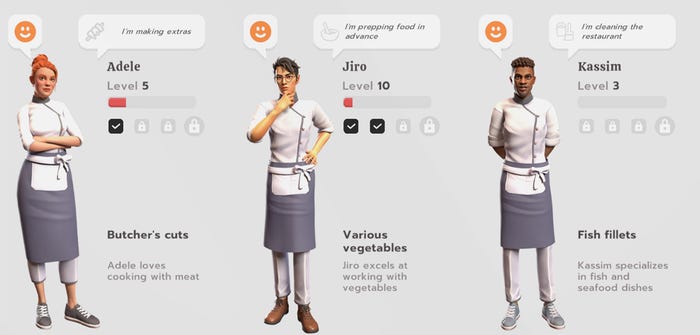

Brigade

The player’s kitchen staff increases as the adventure progresses. We decided to focus on the “feel good” factor by creating a team with characters having their own personality and specific aims rather than focus on management mechanics of hiring and firing dispassionate assistant cooks and a variety of stats. The brigade progresses with the player. At the start of the game, they can only cut up ingredients, but they gradually learn how to manage whole plates. Even though each restaurant has its own way of doing things, we wanted the brigade to become a familiar environment that evolves with the player.

The dream team.

An appetizing art direction

Ingredients

We originally went for a hyper-realistic approach when rendering ingredients, but that created a sort of meat and vegetable uncanny valley, and thus, uneasiness among players because the resemblance was imperfect. Meat that isn’t quite right will inspire immediate repugnance. We therefore adopted a semi-realistic art direction where the accent was put on making ingredients look appetizing rather than lifelike. Images of food we see in the media are often saturated and contrasted to hide any defects. We adopted this approach by using bright colors. Ingredients are rendered in a slightly “hand-painted” manner that produces softer textures. Proportions are globally true to life but adapted to the game’s requirements.

A turnip and cooked beef.

This approach enables us to obtain an appetizing appearance and to reproduce the pleasant experience of eating in a restaurant.

Environment

Kitchens in most restaurants are neutral, with white walls, tiling, stainless steel fixtures and fittings, and neon lights. But when you watch cooking shows, there are bright colors that create a dynamic and warm atmosphere. Chef Life mixes this imaginary restaurant world that places the cook in an environment that is more welcoming and familiar than in reality, with true-life elements.

Real kitchen equipment, such as ventilation ducts, ceiling extractors, and dishwashers, place the game in realistic fantasy. The player can customize their kitchen: an aluminum worktop and base unit or, for a warmer feeling, a wooden worktop and colored base unit, etc. The kitchen opens onto the dining area, making it more spacious and pleasant, as well as bringing more life to the service hours.

Preproduction concept of the open kitchen.

UI/UX

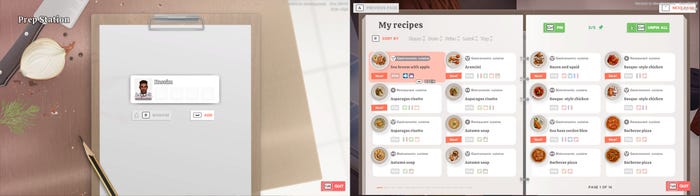

The player must move around their restaurant to access the various interfaces rather than have a magic menu available at any moment to take care of management. We have tried to limit extra-diegetic elements to reinforce the chef’s immersion in their restaurant. Most interfaces are inspired by the 3D environment, such as the recipe book in the kitchen. This allows the player to lose themself in the game experience.

Menus are accessible by interacting with the environment.

Interfaces have a design consistent with what they represent and their location in the restaurant.

Sound

Sounds in the kitchen in the game are realistic because many were recorded during real cutting and preparation sequences in a kitchen.

The sound designers on the project had to find the happy medium between formal and casual for the interfaces SFX. The visual production of the game interfaces helped find this balance: the sounds illustrate the backgrounds (noise of computer, turning pages, etc.), bringing warmth without being childish.

The soundtrack is key, giving Chef Life its funky identity. We opted for feel-good rather than realistic music. The overall atmosphere is lively, funky music that puts the player in good spirits for the day ahead. The music is peaceful in the morning and becomes more and more dynamic as we get closer to the service time.

We hope that the game’s soundtrack will one day be played in the kitchens of real restaurants and that the cooks will hum the tune in a happy atmosphere!

Some final thoughts

If we invested time to go into all these aspects in detail, it was because the game’s promise was appealing to us. The team enjoys cooking, and it was important to adapt this common passion. Chef Life is not a perfect game, but we are proud to have delivered on our promise of developing a game that depicts so many aspects of the restaurant industry that is also accessible to as many people as possible. Our only hope now is that our chefs derive as much pleasure from playing as we did in creating. Have fun and “Bon appétit”!