Game Developer Deep Dives are an ongoing series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren’t really that simple at all.

Earlier installments cover topics such as how indie developer Mike Sennott cultivated random elements in the branching narrative of Astronaut: The Best, how the developers of Meet Your Maker avoided crunch by adopting smart production practices, and how the team behind Dead Cells turned the game into a franchise by embracing people-first values.

In this edition, creative director of Saltsea Chronicles Hannah Nicklin discusses how Die Gute Fabrik’s new story-driven adventure game structures the storytelling so that all ten of its characters can shine.

I have a strong memory of the last year or so of working on our last game Mutazione.

It was back when I was transitioning from narrative director to the studio lead and creative director on our next project. I remember sitting with Doug Wilson, one of the company co-founders, and agreeing that while we loved that Mutazione was a story about a community (and one we’re extremely proud of), there was just one element that we wished we had more time to dig into.

We felt like there was an argument that the form it takes—the traditional adventure game form of ‘single character explores’—clashed slightly with the content. Mutazione is a story about a community, where all the characters are as important as one another. Doug and I wondered: what would a Mutazione look like if you could play each day of the game as a different member of the ensemble?

A story-driven seed

Some of the cast of Mutazione, on band night.

At the point we had this shared thought, we were at a stage of development that would have never allowed such a pivot. Instead, it remained a little seed in our minds: what would it be like to build a game from the ground up that allowed the player not to be asked to roleplay/guide one character and instead to explore a story as a whole cast?

It would demand a whole new production approach, whole new exploration and navigation systems, and much more writing. But it would also allow us to further explore in form as well as content the themes of community and how we live together that we had begun to explore in Mutazione.

As we began planning for a new game, Nils, Doug and I decided to plant that seed—to begin to think through themes and storytelling within games through the eyes of a group (not a ‘party,’ like in RPGs, but a playable ensemble cast in a story-driven game setting*), and how we could use that to thematically and politically underline the things we wanted to say about storytelling and the stories we tell ourselves about the world.

I have often talked about the politics and themes of Mutazione being best served by a ‘multiple middles’ narrative design. Saltsea Chronicles extends that principle to ‘multiple heroes’ or rather, no hero at all.

So, how did we do that?

*There’s more to dig into here with regards to why RPGs aren’t the same as what we’re aiming for in terms of our ensemble cast-driven game, but that’s another article’s worth of thinking. I’ve already written a lot here. Let’s not meander further.

Story pillars

Saltsea Chronicles is a flooded-world story-driven adventure game where you play as a ship’s whole crew. At the beginning of the game, you discover that Maja, your captain, has gone missing, and together, your ragtag crew set out to explore the islands of the archipelago in search of clues.

In each chapter of the game, you will decide where to head next, who to explore with when you get there, and what you say to the people you meet. You can ‘play as’ every member of the crew at some point in the game, and the way choices are phrased and the manner in which you’re invited to engage with the game asks you to consider how you play for and with them as a whole community, as well as individuals.

Right from the outset, when I was drafting key pillars for the game and the game’s process, one of the key pillars was:

This is sociological, not psychological, storytelling.

The pillar read thus:

Sociological vs. psychological storytelling

-

This is an ensemble cast-driven game.

-

Which is interested in distancing the player from ‘role-playing’ in a traditional sense.

-

Allowing the player to feel empowered to customize their crew’s journey through the world while still being surprised at the outcomes.

-

Allowing room for characterization to be authored, full, and surprising—the agency is through exploration, the characterization is authored.

Our storytelling, characterization, narrator, and ensemble cast revolve around two main influences here:

Key influence 1: The Quiet Year, by Buried Without Ceremony.

“We all have two roles to play in this game. The first is to speak for the members of this community, and to care about their individual and collective fates. The second is to dispassionately introduce dilemmas, to provoke difficult situations and see what comes of them. The Quiet Year asks us to move in between these two roles. […] We shouldn’t feel that any single viewpoint belongs to any one of us, and are invited to speak for different community members throughout the course of the game. By explicitly calling out the actors and perspectives of the community, The Quiet Year allows us to explore how individuals shape communities, as well as how individuals are shaped by communities in turn. ”

The TTRPG The Quiet Year invites the player to consider the politics of community extremely effectively through this simple invitation. We will aim to issue a similar invitation in our game and narrative design.

Key influence 2: The sociological/psychological terminology drawn from this article by Zeynep Tufekci on Game of Thrones “The Real Reason Fans Hate the Last Season of Game of Thrones.”

“In sociological storytelling, the characters have personal stories and agency, of course, but those are also greatly shaped by institutions and events around them. The incentives for characters’ behavior come noticeably from these external forces, too, and even strongly influence their inner life.”

We therefore aim to shape a game where the player is:

-

Not invited to inhabit, alter, and reveal the inner landscape of a single character and a world solely shaped by that character’s morals, journey, and experiences.

-

Is invited to shape the conditions through which the community of the crew navigates. In nudging their journey down different paths, the player will discover how the individuals in the community change how they relate to one another and to the world around them. Characters are shaped by the different iterations of their society, and they shape it in turn with their actions.

There were other pillars besides (six in total). But let’s continue to consider this one, and how the game’s design sets out to achieve it.

Humane design, choice, and careful tuning

One of the things we wanted to preserve in the story was the complicated, messy humanness of being a part of a community. Very early on in 2020, we had a prototype of a ‘mood’ system: individual crew moods, which contributed to the overall mood of the crew, with resulting conversations written alternately for the different moods.

But this quickly became obviously the wrong approach for our game. The temptation when we played was always to track and min/max the systems—this meant that, as a player, you stopped thinking about the characters as people, as messy creatures with a weight that couldn’t be represented by integers or sliding rules.

What replaced this quite quickly in development was the Issues system. This was another piece of design influenced by The Quiet Year, in particular the ‘Contempt’ token mechanic. This is how the rulebook of TQY defines the use of Contempt tokens:

If ever you feel like you weren’t consulted or honored in a decision-making process, you can take a piece of Contempt and place it in front of you. This is your outlet for expressing disagreement or tension. If someone starts a project that you don’t agree with, you don’t get to voice your objections or speak out of turn. You are instead invited to take a piece of Contempt.

Contempt will generally remain in front of players until the end of the game. It will act as a reminder of past contentions. Its primary role is as a social signifier. In addition, you can discard it back into the center of the table in two ways: by acting selfishly and by diffusing tensions.

The effectiveness of this mechanic is that it is a nuanced, humane, and flexible act within a very structured game. Other players are not even supposed to speak while the current player acts. But they can communicate the friction of decisions on behalf of the community they’re playing with in this way.

Just like in a game of The Quiet Year, in Saltsea Chronicles, moments in the play of the game will cause tension and friction between characters—sometimes positive and negative all at once! A choice to go to Island A and not Island B will please one person and disappoint another. The Issues are tracked and highlighted by the game. They can be solved (sometimes by single actions, sometimes by a cumulation of moments), but some might never be (and end up ‘scuppered.’)

Your game is not systemically better or worse because of Issues, just as in a game of The Quiet Year, a stack of contempt tokens can’t cause you to ‘fail’—but they do describe a path your community has charted. In a similar way, our Issues reflect the imprint on the world and the characters’ relationships that your choices leave in their wake. They also represent a trust in our players to tell stories themselves, as well as have the story systems underline them. Issues are little descriptive seeds which the player can grow in how they reflect on their version of this story—not ways to win or lose.

The design of choice within conversations was also something we long iterated on. You should see the extensive style guide I produced when I had a final design for it! But to summarize a key point for this deep dive on the pillar of ‘ensemble cast storytelling’: we phrase the choices in a way that is rarely character-explicit. We rarely offer choices which are ‘X says this’ and ‘Y says this.’ When you’re on an expedition, it will be more about the vibe of the response, and part of the pleasure should be finding out who speaks when you guide that vibe.

This contributes to a sense of humane storytelling and not playing as ‘one’ character. You can choose between ‘Quietly’ or ‘Charge in,’ and part of what we hope is the pleasure of play will be seeing how your choices play out; will ‘Charge in’ be the brash Iris, or a surprising character moment for the shy Kittick? It’s also important that you’re never choosing for people outside of the crew. The player is not all-powerful; they are guiding one group through a world.

But in all this, we also needed to maintain a strong sense of character for each possible crew member and give each of them a rewarding level of character development! Let’s dive further into some of the strategies that helped us do that.

The expedition format

One of the big challenges was to balance authorship and agency within the thematic aims of the game. We needed to produce a storied experience that was built of multiple pathways, collective/community storytelling, a clear progression of the central plot, and the mutual development of each individual member of the crew.

This was a tough balancing act! We needed enough authorial control to make sure the player’s experience was coherent and well-paced, but we also wanted to offer choices that felt genuinely rewarding. One of the key pieces of design that support this is the expedition format: it’s as though you’re in an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, and Picard says, ‘Number One: you lead the mission, form an away team.’ We’re the writers of the episode who have given you a crew of characters to choose from, and you’re a devilishly handsome first officer who will decide who will explore the location.

To keep the storytelling coherent and to balance the character development throughout, we have shaped the story of each community around a lead expedition character (usually because of their skills or history with a place); this means that we know every character gets a fairly balanced crack at the whip of being part of the story and to be developed by it, though your choice of locations to explore will also play into this. And it allows us to use genre-based storytelling to keep the world of the game approachable and comprehensible. So, if you choose X location, we know Y will lead, and that it’ll be in Z genre. As writers, we therefore know the headline possibility space for each character’s development. These knowns help us give you a strong, storied experience.

Then, the secondary expedition character is your choice. There can be up to four possible secondary expedition characters (depending on who you onboard and where you go). In the screen where you choose the secondary character, you can compare their aptitude and motivations in the character select screen. None of the choices are wrong, but they are important because they shape the story in the player’s mind and the crew themselves (in humane, not min/max ways).

So, for example, in the first chapter, Murl leads the expedition. We chose him as a writer’s room because he’s a loveable, stuffy historian, and the character and voice are very recognizable. It gives the story a strong first hook for a player new to the world. Then you can choose between a local moody non-binary teen and radio specialist Iris, or a practiced diplomat and adventurer Stew (she/her), who is much richer in years and experience but not a local. Neither will hinder the player’s progress, but it will shape your experience and how people talk to you.

There’s also the Boat as a place for careful character development. Island locations demand you select certain characters to develop, but we account for those choices by allowing you to re-balance your story on the boat where the whole crew is gathered. So don’t forget to explore how people are doing when you return to them!

The challenge of tuning a journey for all the characters that also rewards choices was tough; the boat aims to hold that together. It’s okay if you’ve preferred to focus on a couple of characters over others—that’s your playthrough—but the others’ journeys will hopefully still be strong ‘B’ character developments to the ‘A’ character decisions you made via the Boat scenes. This allows us to shape a story of ‘multiple middles,’ which is both authored and built around the player being able to guide a crew (not just a single character).

For more on ‘multiple middles, ‘ check out this blog post where I develop thoughts on it as a narrative design principle in the storytelling of Mutazione.

Finally, I’ve talked about how The Quiet Year impacted the design of the storytelling in the game. Then there’s the Next Generation/Deep Space 9 era of Star Trek and the masterful mix of monster-of-the-week and ensemble cast storytelling, influencing how we thought about how we structured the story episodically through genre. Let me introduce a final aspect: our philosophy around NPC agency. One thing I did early on was to invite the story team to consider Avatar the Last Airbender in terms of how we approached the communities the player visits as they travel. One of the biggest strengths of Avatar the Last Airbender is that the cast are tending to others’ troubles as often as Ang and his pals try to further their own story. (There’s also this brilliant Meghna Jayanth piece from a while back on NPC agency.)

This idea of NPCs sometimes having problems you can’t solve (or refusing to serve you), along with the Avatar the Last Airbender principle of ‘give as well as take,’ formed part of my ask for the writing team: that communities will have their own life, that time will move on and they will move and change regardless of your smaller actions, and that you will spend time helping people as well as moving the mystery forwards: simple principles that formed the backbone of the structure of each chapter, defined how time works, and shaped the stories told in each location.

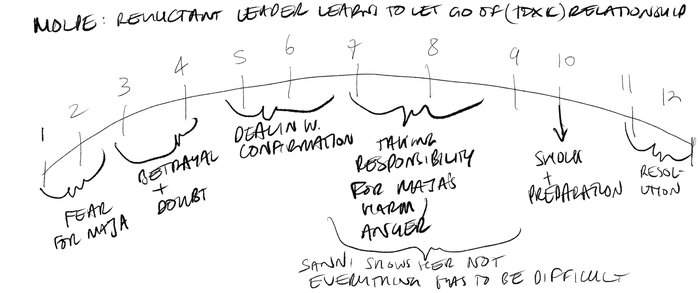

A hand-drawn beat sheet for Molpe’s main moments of character development mapped to chapter numbers

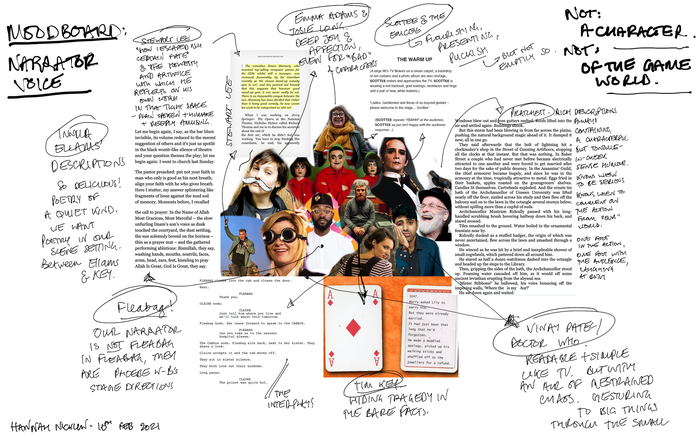

The narrator

The presence of the narrator was also part of our statement of intent around ‘community over individual.’ The narrator’s voice is part of shaping a distance from the crew and the player, which allows you to see them as a whole, discreet from any roleplaying tendencies you may have from other games.

We don’t want you to care less about the characters, but we do want you to think about them as both community and community actors. We don’t want you to immerse yourselves in one of them; we want you to interact with the complexities of them as a group. Immersion is a process of washing away your world and self and replacing it with another. There’s nothing wrong with it as a storytelling tactic, but it’s not useful in our case. The kind of interaction we’re interested in asks you to think about community as well as individual—and needs you to stay one step back, to think of the system as well as systemic acts.

These punchy overlaid interjections are always either direct quotes from NPCs, or the narrator’s observations

In those terms, the presence of a narrator—positioned somewhere between the action of the story and the player—allows us to situate you in a place of interaction rather than immersion. Of course, a good story of the kind we’re trying to tell will always make the background of your life fade away as you get wrapped up in it (we hope!), but we never want you to pretend you are one of the people, we want you to guide these rich characters as yourself.

The narrator, it turned out, also allows for far more than that besides: both a ‘show, don’t tell’ level of visual detail—sudden, tiny changes in people’s faces, gentle touches of the arm, things we couldn’t afford to animate could now be described—and a gentle extra level of humor. The narrator isn’t far off Terry Pratchett’s famous footnotes. There’s a whole piece of documentation on the narrator’s voice too. It’s a bit too extensive to include here, but here’s a sneak peek from my documentation as I tried to communicate my vision for the ‘voice’ of the narrator via other examples/voices.

Replay by design

In Saltsea Chronicles, the theory of multiple middles retains many of the same principles seen in Mutazione. It’s important to us, for example, that the player isn’t cast as ‘god’ in the story and that the agency of the rest of the world is strong. Likewise, in Mutazione, instead of multiple endings, you’ll uncover multiple middles. Your path through it—who you get to know the most, who you meet, the way you color your conversations—will be yours.

But in developing this further in Saltsea Chronicles, a new aspect we explore is greater variability and possibility space for storytelling. In that sense, the mystery the player uncovers is the same mystery they’ll share with all players: ‘watercooler moments’ you can share with others. But your pathway through the mystery is yours, even down to who travels with you and who makes it to the end. We hope you’ll be excited by what you uncover and how you uncover it. The former you’ll share; the latter will be in your hands.

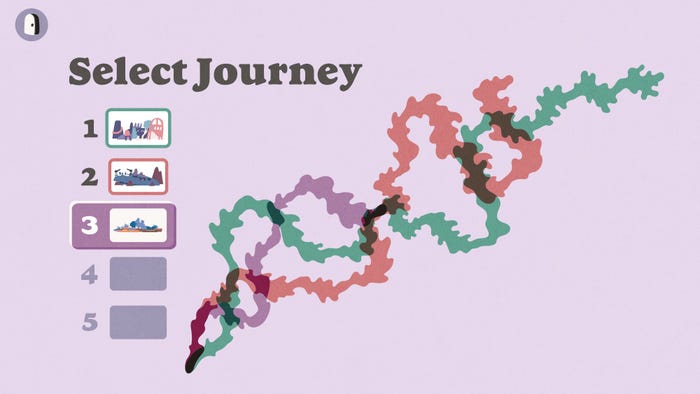

To support this, we’ve made that explicit in the design of our save systems and the tools we give you to play in those multiple middles. Instead of exploring the middles solely by exploring space and time as in Mutazione, we’ve dramatically increased the possibility space via the different scales of story acts you can take: choosing a location and choosing an expedition character (before you get to individual conversations and space and time).

An early mock-up for our save system (which looks quite similar but a bit more beautiful in the game)

We wanted to surface this for the player visually. And also—because part of the pleasure of play is in exploring the possibility space—to make sure it was easy to explore alternate pathways through the story. So we produced a save system that describes the headline choices you make (location and expedition character) as branches in a piece of seaweed, and made it so you can ‘branch’ your save journey from any chapter of a previous playthrough. You can see your pathway described and retrace your path to try another branch.

If you finish a journey but wonder what it might have been like to make a different decision at the end of Chapter 2, end up in a different place in Chapter 3, then you can do it with a few taps in the save system, all without having to start a brand new save. We want to invite the player to delight in the possibility space we built for them; in exchange for locking you out of being ‘god’ in the world, we give you play.

Writers’ room

Finally, a thought on process: video games are not only made in design decisions but in the design of the processes by which they are made. One of the principles upon which I built the studio under my leadership is ‘excellence, intentionality and care’—and I like to be clear, that’s not just in what we make but in how we make it, too.

It was clear to me that a story about a community—a story that I hoped would be rich and diverse—needed to be built by more than one person, one perspective. A core part of the design of this project, therefore, centered on bringing together a writers’ room over several different phases—worldbuilding and story development, and two phases of writing. There were also entry-level paid internships built into the process so we could bring in experienced people from different disciplines and fresh voices and perspectives.

Every member of the writers’ room has left a mark on the story, world and characters—from Njarfie Roust bearing a resemblance to Josie Giles’ home island of Orkney, to Sharna Jackson’s experience of actually living on board a boat in Rotterdam, to Ida Hartmann’s wonderful and weird imagination giving us names like ‘Gertleshraub.’ The room and process were led by the steady and experienced hand of Char Putney (The Divinity series, Nuts) and brought together people from poetry, young adult fiction, theater, film, TV, and more. We even have someone who won the Arthur C. Clarke Award during the making of the game!

Building a world of collective solutions and also taking time to not build into that world some of the unthought biases and assumptions of our world was something carefully and collectively done, and I hope that you see all of that hard work in the rich environments, wonderful characters and colorful locations you’ll discover as you play. And, of course, it’s been brilliantly brought to life by our art and animation team. You can read a perspective from one of our writers on our worldbuilding in this lovely blog post here.

We also needed all those people (around ten story folks in total over the project) to produce this game. When you choose one expedition character over another, several other versions of that chapter are no longer part of that playthrough. There are somewhere between 350,000 and 500,000 words in Saltsea Chronicles that make this possible, all carefully considered, tuned and crafted to serve the goal of collective storytelling.

There’s a version of this game that could have been done with procedural systems, but another core principle was ‘our key innovation is shit hot writing.’ That means time for members of the story team to come on board, learn the ropes, write, rewrite, edit—and systems clear and simple enough for new folks to join and contribute—including people who hadn’t worked on a game before (keeping our team, and the worlds we wrote, diverse and excellent). This necessitated a simple use of a writer-readable tool (Ink), super-thorough documentation, and clear structure for the storytelling—defined from the outset. We could, therefore, hire from a wider pool of writing talent (not just those with procedural/systemic experience or aptitude) and maximize our time to ‘just write.’

Shout out to the careful work that was laid in the foundations by Katrin (our programming lead) and Char (story lead), who built a space for writers to write, and to the whole story team for the documentation that we all collaborated on to support it. We developed a workflow that was well-structured and well-understood, and made sure to build in reflection for us to work out when it was time to move on, to cut, or to pivot. We also clearly defined the roles each member of the story team took on, story techs who built the infrastructure of each episode, the story-definers who pulled together the specific parts of each chapter, the writers, editors, and QA, not to mention all the art and animation, music, programming and production team whose efforts also brought it to life.

I won’t trifle with your patience further by naming everyone from the team here, but do check out our People page, which shows the main actors in our team.

A story without a hero

Hopefully, you’ve enjoyed this deep dive into several angles on how we’ve tried to develop a means of telling a collective story with this new game. And rest assured, it’s also in the content of our story too. Saltsea Chronicles doesn’t tell a story about a hero; it’s a story about a community and how we navigate the world together. Form and content, people in context.

Each community you visit will be rich, wonderful, amusing, and have its own things going on. There are plenty of laughs, but tough choices and meaningful moments too. Our writers’ room of award-winning storytellers has really woven some magic.

We’re so excited to discover what paths you chart when you play.

In the meantime, please, buy the game on Steam, PlayStation 5, and/or Nintendo Switch!