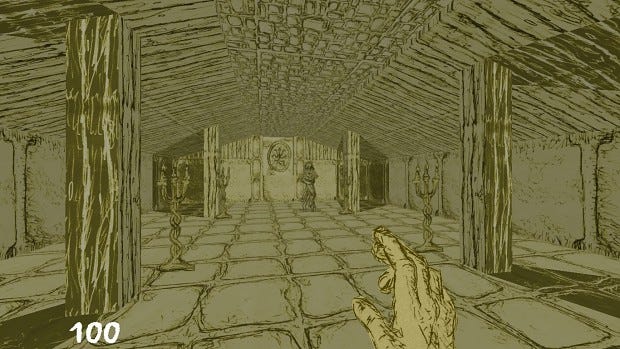

There’s an immense charm to games with hand-drawn illustrations; 2021’s Mundaun, for example, was well received for adopting a pencil sketch visual style, which imbued the game with a visceral texture that seemed to reinforce the rough-hewn edges of its dark religious folk horror. Like Mundaun, He Came From Beyond is drawn by hand, but with an added challenge: all of its assets were first scribbled on a Post-It note. This Doom mod is coming together as over one thousand scraps of tiny yellow paper, the culmination of the whims of a first-time developer who one day got an unusual idea. Polish designer Michał Puczyński tells us how the greater Doom mod community has helped him bring his vision to fruition.

Game Developer: Is this your first game? Do you have any education or background as a game developer? Or are you a traditional artist?

Puczyński: I don’t have any art education, and at the time of starting this project, I didn’t know anything about game development. I happened to like Doom, and at one point, I downloaded its modding tools and simply started playing with them.

At first, I started making a tongue-in-cheek sci-fi shooter called Heavy Metal Armageddon, where you’re an angel sent to wipe out a civilization that became corrupted and evil.

But since it was my first project, it wasn’t very good. Also, I relied on existing Doom assets, stock imagery etc., so I didn’t feel it was truly my game. I wanted to make something that would be 100% my own. I decided to start anew with an idea that I had. I had these sticky Post-It notes and I realized they kinda look like a blank Doom texture. I like doodling, so what if I doodled something on a Post-It and scanned it into the Doom engine?

That’s how He Came From Beyond started. Everything in the game was determined by this style. For example, the pacing or the gameplay. I couldn’t have overly sprawling levels because the style is so demanding that it takes months to complete one map. So the character couldn’t move too fast. So it couldn’t be a shooter anymore, and so on. The story takes place inside a diary because it made sense to have this framing device with this style.

But He Came From Beyond won’t be the first game with my name in the credits. Recently, in an unexpected turn of events, I was asked to run Road Studio, the team working on Alaskan Road Truckers, a game that’s going to release later this year. That’s also why my work on He Came From Beyond has slowed down. Weirdly enough, both He Came From Beyond and Alaskan Road Truckers are set in Alaska. It’s like fate wants me to make games set in this state.

Your game has such a distinct visual style. What inspires it?

Have you seen horror movies where a character finds some kind of a diary or wall scribbles that look strange and wobbly, made by some kind of a madman? I was watching something that had it and I thought: that’s an interesting way to see the world. Imagine a game where you look through the eyes of a person that perceives everything this way.

Also, my hands are naturally shaky, so I’m not good at drawing straight, precise lines. I decided to use it to my advantage, hence the rather chaotic, trembly look of everything.

Why did you choose to draw the game on Post-It notes? What tools do you use to compile a large image from a series of very small ones? What process do you use to translate these small scraps of paper into a much bigger, 3D environment?

Well, a Post-It looked like a blank 64×64 texture to me, and I was curious if I could simply scan it to the game. Turned out I could!

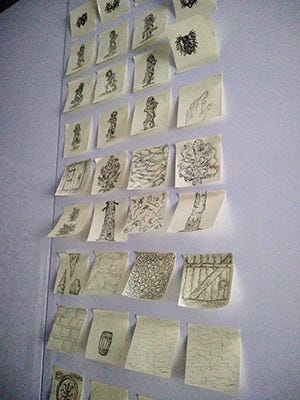

So I draw something on a yellow Post-It, then scan it and get angry that the scan loses its yellow color and turns out blue for some reason. Maybe it’s my scanner. Then I even out the contrast and restore the color in GIMP and use Slade 3 to put it into a project for the GZDoom engine. It’s super simple, although I used larger drawings for a couple of things like backgrounds because trying to compile them from a series of Post-Its was a nightmare. So there are, like, three drawings in the game that were made on A4 sheets, but generally, a square sticky note becomes a 512×512 texture or sprite.

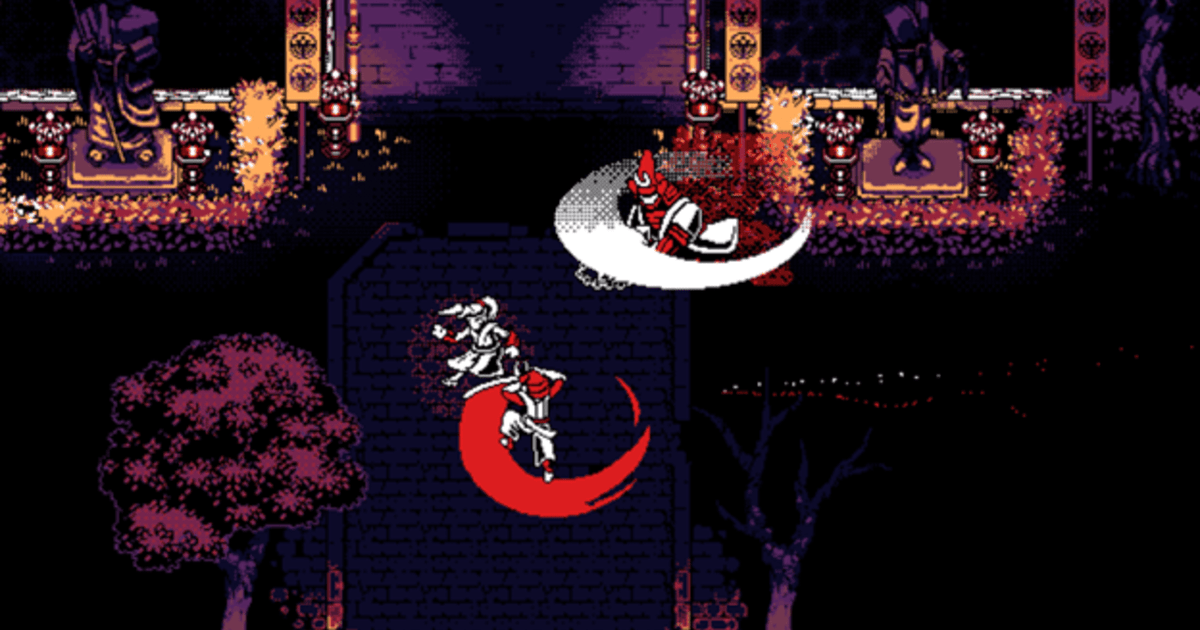

There are no technical tricks in the game. It’s just 3D levels with walls plastered with scanned doodles. Enemies and objects are sprites. The entire game is extremely simplistic from this point of view. I don’t know how to program; I just learned the basics of the Zscript language, which was made specifically for Doom. When I need to do something more demanding, I often get help from some great and experienced people from the Doom community, but I want to keep it as simple as possible. I use what’s already in the engine in ways that may be unusual, but I don’t invent any new tools etc.

How many Post-It notes do you suppose you’ve drawn so far?

Welp, I think I’ve used about 1000+ Post-Its. In the game, there are currently around 1600 separate visual files, but some I’ve managed to do on a single sticky note. I didn’t even realize it was that many; at first, I thought it’d be like 500 at most.

Do you keep all of the Post-it notes afterward? Where do/would you even store them?

I kept the initial sticky notes, a full picture album of them, but once I used up all the space in it and realized this isn’t even half of what I’ll need, I started simply throwing them away. It’s not like it’s high art, so I don’t miss them too much. I can draw them again if necessary. It’s the effect that matters.

What’s difficult about it is that these bastards don’t scan in an even manner. Some come out darker, some brighter, and tweaking their look in GIMP is a huge undertaking. My goal is to make screenshots look like drawings. At least some of them—I came up with inverted colors which serve as shadows here and there.

I use these inverted colors for areas where not having them would make the picture too messy. Shadows help recognize depth. It’s something I learned the hard way. It compromised my idea of it being like drawings, but it was necessary. Also, alien worlds are presented only as inverted textures to add strangeness.

What can you tell me about the developing story? How do the game’s narrative and aesthetic themes support one another?

In general, I am a huge fan of classic horror books. Lovecraft, but not just him. I read everything from Algernon Blackwood to Mary Shelley, Robert Chambers, Arthur Machen, to Robert Louis Stevenson. I have a stack of books that I read specifically to prepare to make the game. They’re so fascinating! I love horror that is beyond comprehension and/or involves some kind of metamorphosis into an inhuman thing. In a way, it’s very optimistic because it assumes that there’s more than the world we know, and also that evil can be separated from humanity, that it’s not just us. So yeah, the story was inspired by all of this.

The core idea is that you wake up reborn, anew; it’s the first thing you read in the game. You are a blank sheet, literally. You wake up in an underground place, the function of which you have to figure out yourself. There is a nearby town where you discover you are in an Alaskan mining settlement in the 1920s. The town is almost empty. It was bought out by a strange bunch of rich people who investigate paranormal activity for fun. It seems that here, they found a real thing.

From the beginning, you know that all of this leads to a choice that you’ll have to make at the end. The choice will be quite clear, but the implications of it, well, that’s something you have to judge yourself. I hope the ending will be a surprise and leave you with something to think about.

The war in Ukraine had a big impact on the story. I live in Poland; I see refugees every day, I see news about it, etc. In the game, there’s a war angle too, and I think because of this, it became a bit darker. It’s a horror with weird creatures where the most dangerous enemy is a human, and I find it bitterly funny in a way.

What does the narrative and gameplay structure look like? Is it more of an exploration-driven experience or are there any puzzles involved? You said earlier that certain design constraints meant this could not be a shooter, but the game still has enemies, so I assume there must be an additional game mechanic there.

It’s definitely not a shooter but there’s action in it. There are enemies, but I’d rather have fewer of them and make them memorable and truly difficult than spawn a bunch of them as cannon fodder. You don’t have a weapon per see, but you use your special ability under the fire button to, hmm, communicate with everything around you. You can affect enemies and the environment this way. Maybe you saw a screenshot with the protagonist’s hand, which has an eye on it, and later also the sixth finger. There’s something inside you and it can do things. This also ties to the progress in the game. It becomes a bit more action-oriented later, when you improve said ability.

There are puzzles, sure, like when you have to push all the buttons but pushing one down makes another go up. Or you have to align certain blocks so they make a path. Or you have to light an incense burner but you need matches and incense powder. These aren’t very complicated because I don’t want anyone to get stuck on a mind-bending puzzle. They’re there to give you a sense of achievement and progress.

There’s a lot of things to interact with and that’s the way the story is told. There are cutscenes, inside and outside of the diary, and they’re the best thing to make—it’s a lot of fun. Many things are communicated by short descriptions and you can talk with characters. It’s all written in past tense and dialogues use indirect speech (because you’re reading a diary, not a novel), and I think it gives the game a certain flavor. To make it a bit Lovecraftian, I avoid contractions just like he did in his writing.

As for the overall narrative structure, I wanted to use the fact that you’re reading a diary. So while it’s a linear sequence of events, some of them you don’t fully remember so there are, for example, blank spaces in a level. Or perhaps a torn page, or something is crossed out. The narrator tries to explain the events he (or she) experienced objectively, so he doesn’t judge them, a lot of things are just described and you’re encouraged to interpret them yourself. Are they real? What do they mean, considering the big picture? Dialogues are frequently shortened to give you the gist of the conversation: “She talked for a couple of minutes about X or Y.” I think it’s fun to have this memoir-like narrative because it gives you room to do unorthodox things with storytelling.

The idea is to let you make a choice at the end, but what the choice really is and what are its implications—that’s for you to decide.

What do you think is the next step to move the mod forward? Do you have a collaborator for audio or are you doing that yourself?

I work with quite a team. Beni Harper is doing sounds; he’s a professional audio specialist working in the movie industry. He’s been kind enough to join the project because he liked the idea. I think his work is outstanding; it adds so much depth to everything. SC, from the Doom community, is helping with scripting. Music is composed by Trystan Jongejan and Voltamass, who are both fantastic. In the case of Trystan, who I’ve known longer, it’s often that his music inspires my design.

The project is also supported by Calcium, Ulises Serrano, and some other people who I’m not sure would like to be mentioned by name or nickname. Without them, the game wouldn’t be possible, because they help me solve problems I could not solve myself, or in the case of Beni or SC, they have creative input as well. But since everyone’s working on it after hours, for free, it’s taking time.

What the project needs now is my time since I’m doing all the art, design, story, cutscenes, enemies etc. If I block it, everything is blocked. This year was super slow for He Came From Beyond since I’m working on Alaskan Road Truckers and it’s in the most intense part of development. I simply don’t have time, or frankly energy, to work on another game after hours. But I’m thinking about it all the time. The work happens in my head, which is good, because I have more time to think over every aspect. And since I don’t have any deadlines and I don’t consider this game a source of income, I can take all the time I need. This may upset some people who want to play it as soon as possible, but this is my #1 rule for this project: I only work on it when I really feel like it. I hope this results in something truly inspired.