Game Developer Deep Dives are an ongoing series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren’t really that simple at all.

Earlier installments cover topics such as the starkly stylish art direction of Bloodless, how GOG updated Alpha Protocol for modern digital release, and how Ishtar Games approached the design of a new dwarf race in The Last Spell.

In this edition, Joseph Humfrey of inkle tells us how the studio was able to give players a dynamic photo mode in a 2D game.

Who doesn’t love a high-quality photo mode in a stunning game? They’ve mostly been the domain of 3D games with ultra-realistic rendering, letting players set up virtual cameras like high-end DSLRs, dial in exposure settings and focus like a pro. But we decided to add a photo mode to our 2D indie game, A Highland Song. Does adding a photo mode to a 2D game make any sense? Surprisingly, it can do, yes! But only if the player is given the tools to create something more than a simple screenshot.

At inkle, I have a lot of responsibilities, but one of them is art director across our various projects. Ever since we made 80 Days, I’ve aimed to make “every frame a painting,” a concept popularized by the YouTube series Every Frame a Painting by Taylor Ramos and Tony Zhou. The idea is that you could take any frame of a movie and hang it on the wall because the cinematography is so beautifully executed. For 80 Days, despite the game being predominantly text, I wanted every moment to look like a 1930s art deco travel poster. (The folks behind Monument Valley, a contemporary of 80 Days, were thinking along similar lines. They loved the idea that any level from the game would look stunning as a work of art on your wall.)

A screenshot from 80 Days. Images via Inkle.

A Photo Mode takes this a step further, inviting players to contribute their creative input to the framing and composition of a shot. While Monument Valley is intrinsically beautiful (and indeed, they have a built-in snapshot button), a photo mode puts the onus on the player to find and bring out moments of beauty. I’d argue that photo mode has been limited to 3D games, not because they’re more beautiful, but because the six degrees of freedom are key to providing that freedom of expression.

Photography fascinates me because it communicates an idea without direct control over the subject. You can line up a photo to juxtapose contradictory objects or create a feeling of movement in a two-dimensional frame. You can tell a story using spatial relationships: a tiny ship on a wide ocean beneath a vast sky; the claustrophobic space between skyscrapers; or a hawk captured dead center, just before it closes its talons around a sparrow. Photography is about choosing your moment in time and space, and finding a point of view that forces the viewer to see what you want to show them, finding beauty even in the mundane. This is what we allow players to do in A Highland Song. You can’t control the mountains, where they are, or what ruins you near to—unless you move your feet.

Stacked highland layers in Unity editor. Image via Inkle.

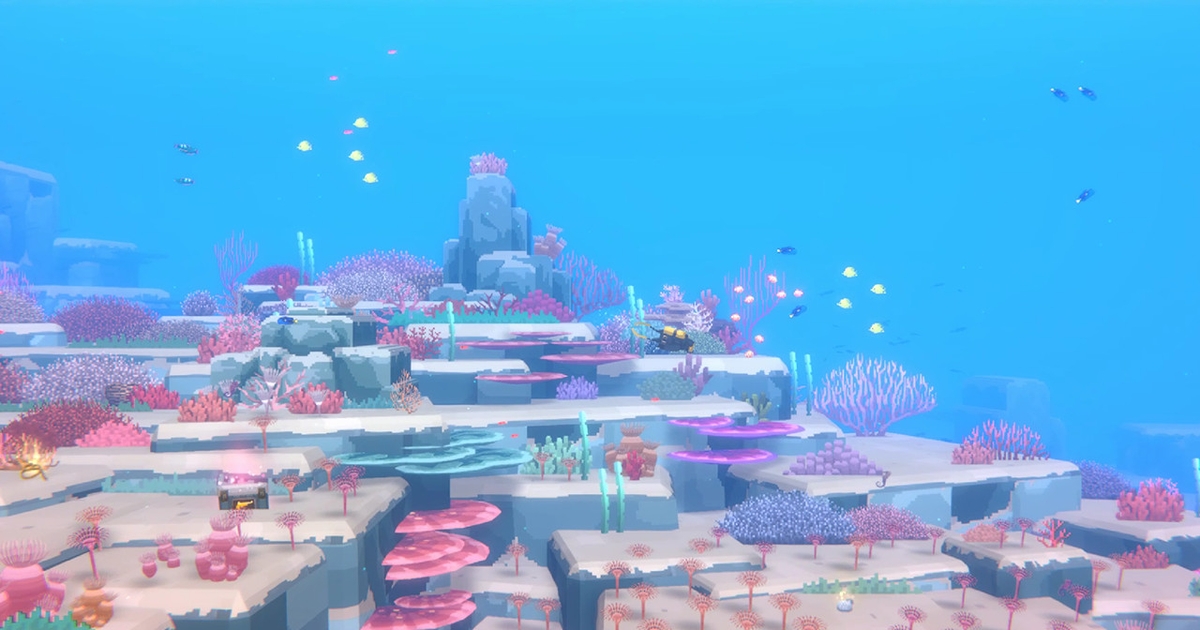

Our secret with A Highland Song is that it’s not fully 2D. It’s built in 3D in Unity, using our own custom tools to stack tens of thousands of flat layers over miles on the Z axis. When you start the game, the mountains in the background are actually all the future levels in the game, extending away from you, leading to your goal: the lighthouse by the sea. The majority of those thousands of flat layers are traversable—this is the “if you see it, you can go there” of 2D games! Our protagonist Moira can hop between the individual layers, wherever they touch. (I’d call this 2.5D, except I’ve been told by Correct People On The Internet that 2.5D is strictly defined as fully 3D art with movement limited to a 2D plane. Shall we stake our claim over the term “2.4D” then?)

This extra dimension allows for a more rich ability to place the camera. While the player isn’t given full rotational control, the freedom to slide the camera on three separate axes does give them creative control over aligning and framing objects in the world. The camera can be also moved into positions that the in-game camera never naturally reaches, such as close-ups of Moira’s face.

A Highland Song concept art. Image via Paul Scott Canavan.

Although we didn’t plan to include a photo mode from day one, we always aimed for a painterly art style, making screenshots look like digital concept art from artists such as Craig Mullins. We worked with the brilliant Paul Scott Canavan to develop the overall art direction, building layered fragments of paintings at various scales—whether swooshes of grass, detailed rocks, or impressionistic textured paint splats. Rendering these fragments at a range of scales meant we could pull the camera in and out dramatically, maintaining the overall style and the visibility of individual brush strokes.

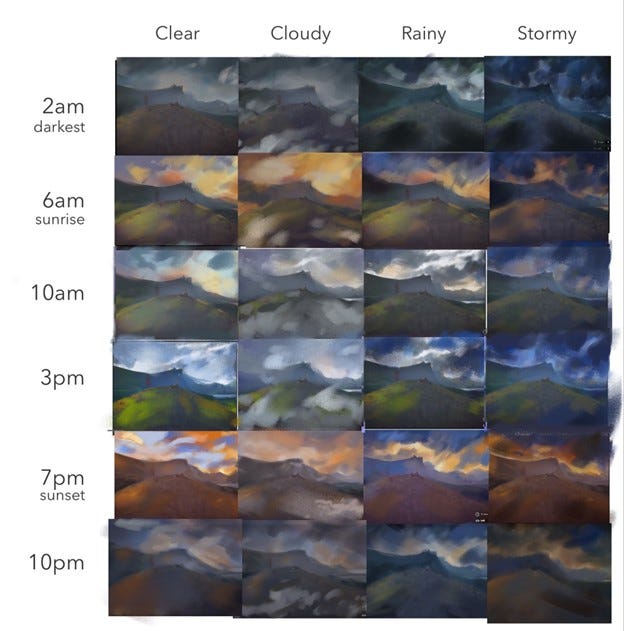

At inkle, we love a good day-night cycle in our games, and this was especially important when representing the mountains of Scotland. A strong part of the Highlands’ beauty comes from the ever-shifting light and the notoriously changeable weather. So, a key feature of our custom graphics tech needed to be to cope with all the possible permutations of time of day, fog, cloud cover, and of course, rain and snow. For example, we have a custom fog algorithm that uses multiple color stops blended over camera distance, and this gradient is then interpolated over both time of day and weather type. It’s not physically based rendering; it’s fully artist-driven to allow us to handcraft the color palette across all conditions.

The color palette used in A Highland Song. Image via Inkle.

Our photo mode reflects this and gives the player control over it: it lets players step outside the game’s narrative reality and play god with all the lighting and weather variables, allowing for a huge range of visual effects. We also allow players to make basic adjustments to exposure and tint in the final image.

All this control gives players significant creative freedom, far beyond taking a simple screenshot. One really fun feature we’re especially proud of is the ability to choose dialogue lines for Moira, our protagonist. The game remembers the past ten lines she’s spoken, allowing players to cycle through them. While you can’t put any words in her mouth, you can change what she says in a particular moment based on her past lines. This gives players a bit of creative control with interesting restrictions, maintaining the core voice of the character. For example, if she just said “Christ on a bike!” after falling a couple of minutes ago, you could reuse the line as a huge eagle swoops down towards her on a mountain-top, creating your own composition out of game-provided elements.

Image via Inkle.

Most games apply these creative constraints to camera movement too, and A Highland Song is no exception. We limit camera movement to keep Moira in frame and to prevent players from sneaking a peek at the game’s behind-the-scenes magic. Since we unload levels as the player progresses, we need to ensure the camera can’t move backward too far, avoiding any embarrassing exposures.

We’re really pleased we chose to incorporate a Photo Mode into A Highland Song (just a couple of weeks before release, no less!). It may not suit every 2D game, but with enough creative freedom, it can be hugely valuable. It provides an extra layer of enjoyment for fans, who then share their work on social media, bringing the game to new audiences.